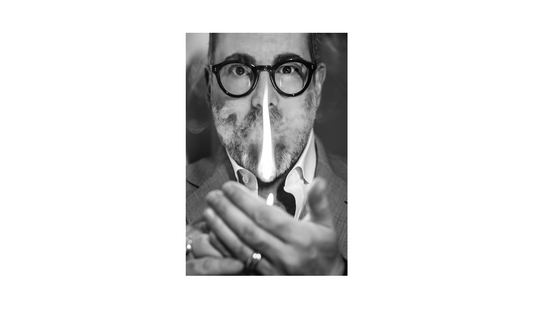

“There are two things a man never forgets: his first cigar and his next cigar.”

—Edward Sahakian

THE NUMBER ONE query I receive via social media is: Which is the best cigar? I always respond emphatically: There is no such thing. There are, rather, only special cigar moments fostered in large part by extraordinarily crafted cigars (though not even always by them).

Keep in mind something I’ve written previously: “Taste-wise, one man’s hand-rolled tripa larga Cuban or Dominican might be another’s Dutch or German machine-made.” So while there is no best per se, there are wonderfully consistent cigars. And if you regularly partake of cigars, once you find a favorite (or two), they’ll be your personal best—or at least your preferred go-to.

The very word best denotes subjectivity, and as such must be predicated on arbitrary personal taste and preference (either by an individual or a committee of the like-minded). Yet this in no way contradicts the indisputable fact that some cigars are simply better than others—sublime ones rolled with significantly aged tobaccos, say, or from remarkable terroirs. Such premium and ultra-premium puros (or multi-origin blend cigars) are—with as little bias as I can muster here—archetypes of the craft, exemplars of the art and technique of cigarmaking. But there will never be a single one that towers over all the rest.

The art of the cigar is multifaceted. Topping the list of variables that makes one cigar more extraordinary than another is continuity of flavor profile—the cigarmaker’s ability to perceptively replicate the blend and smoking experience year after year, decade upon decade, regardless of good harvests or bad, high tobacco yields or low and much else besides.

The second key component is consistency of quality construction. Blend continuity and production quality are objective, while a smoker’s particular flavor-profile preference is individually dependent and thus subjective.

A quarter-century ago, for an intimate Millennium New Year’s Eve fête we were hosting, a good friend of mine—a fellow cigar devotee—together purchased a mostly intact (21 of 25 cigars) box of 1961 Montecristo Number 1s. The box came with impeccable provenance, with a Canadian cigar revenue tax stamp with the year rubber-stamped atop the paper label.

The day before the party temptation got the best of me—Y2K anxiety was in the febrile air, and the world might be ending in 36 hours, after all—and I lit one up. I had smoked many Monte 1s throughout the ’90s and was quite familiar with the classic blend in that format/vitola.

What was most striking was that going on four decades later, the ’61 was utterly evocative of then-contemporary versions despite the fact that the wrappers were not the same. (When the last leaf was picked during the 1996-97 tobacco harvest, an era ended. Corojo—the “World’s Best Wrapper,” which had sheathed Havanas since the 1930s—ceased being cultivated by Cubatabaco growers—los tabacaleros de Cuba—due to its blue mold susceptibility. It was replaced by hybrids.)

This empirical observation would likely not hold true in today's context… In post-pandemic Cuba the ‘classic Cuban blends’ have been forsaken and replaced by a more uniform/homogeneous blend approach for the standard production (vitolario) offerings.

Nonetheless, the December 30, 1999, cigar, and the one I smoked the following evening (to celebrate the fact that airplanes were in fact staying aloft, computer systems weren’t crashing, among other things) became exceedingly noteworthy cigar memories. For me, anyway. Yet I’d be remiss to call either millennium Monte the best. After all, the best cigar is typically the one currently in your hand.

Likewise, the most memorable tend to be those enjoyed during a shared experience or an awe-inspiring moment in one’s life. The vintage Dunhill Havana Club I smoked outside the hospital the day my daughter was born—like the party-like-it’s-1999 Monte—are two such cigars for me. Best is in the eye of the beholder, and indelible memories can crop up when you most, or least, expect them.